7 things you need to know to start planning your day in Hatteras Island – A dingbatter’s guide

OBX, where coastal legends are born – Part 4 – Hatteras Island, Stop 3

Estimated reading time: 16 minutes – SBFL 20* – PLANNING TO VISIT – What’s a dingbatter? Well, let’s talk about that a bit later.

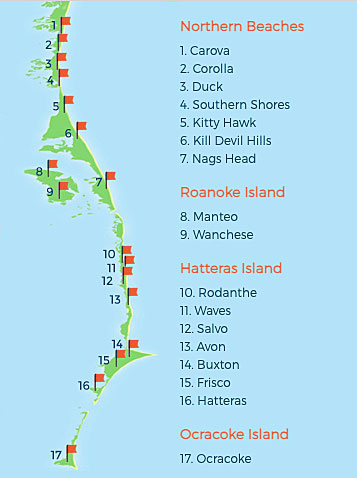

If you are contemplating how far you should go down Hatteras Island, let’s talk about what more there is to see on the island. On our Stop 3, we will:

- Visit 4 villages: Avon, Buxton, Frisco and, at the southernmost tip of the island, Hatteras,

- Catch up on some area legends, and

- Definitely talk about notable spots.

We will be doing this leg of the trip by car, just like the editors of the National Geographic in 1958, our source of inspiration.* I do not see us going to the Outer Banks (OBX) with our boat under any circumstances. When you take into consideration the ever-shifting sands and shoals of the region, for us—fair weather coastal water boaters—I feel that it’s too dangerous, with a high potential for grounding. A case in point, just recently Alhambra, a 37-foot sailboat, was safely grounded just north of Cape Hatteras National Seashore’s Avon Fishing Pier in Avon. Hence, we will continue our OBX excursion from Elizabeth City by car.

We’re continuing to scratch the surface of the many legends and great travel locations of the OBX. On this leg, we’re near the end of the OBX, the barrier islands off the coast of North Carolina. It’s a 128-mile long ribbon from Carova Beach on the North (36.5141° N, 75.8653° W) to Ocracoke Island on the South (35.1146° N, 75.9810° W), separating the Atlantic Ocean from the mainland on the East Coast. Our Stop 3 starts with Avon, then comes Buxton, Frisco, and finally Hatteras.

Avon, the center of Hatteras Island

The alternate unofficial name of Avon is Kinnakeet. It’s an Algonquin word that means “that which is mixed.” The “mixing” was the intermingling of Native Tribes and English settlers there, an important mark in the settling of the Outer Banks and the colony of North Carolina. The name Kinnakeet was made official in 1873 with the opening of the Kinnakeet Post Office, though in 1883 the name was changed to Avon. As of the 2020 United States census, there were 832 permanent residents, 328 households, and 83 families residing in the village of Avon.

Historically, like its neighboring villages, Avon relied on the waters of the ocean and the sound for a way of life, but rather than fishing, boat building was the main industry. This was made possible by the forests of cedar and live oak trees that grow in the area. These trees were key in boat building from the Colonial days to the decades after the Civil War.

What makes Avon the center of Hatteras Island is having the island’s only chain grocery store and a couple of popular chain fast food restaurants, along with its own local establishments, including the Avon Fishing Pier, Koru Village and Spa, the upcoming Avon RV Resort by the Sea, the local medical center, and all the amenities and attractions of a good Outer Banks beach town. The Avon Fishing Pier hosts Hatteras Island’s Independence Day fireworks, which are launched from the end of the pier on July 4th.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is calling you

Well, I can tell you that the famous lighthouse is in Cape Hatteras. As a matter of fact, after Avon we are near the location of America’s Lighthouse, a.k.a. Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, that I have written about in my previous posts. It is located on Hatteras Island in the village of Buxton, and is part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Before you get confused with references to the name Hatteras, let me first clear up any potential points of confusion that you may have so we can move on to Buxton village. By now you know that there is an island in OBX named Hatteras. Hatteras Island is one of the islands that I have been writing about and planning to visit in OBX. That is not to mention the village of Hatteras on the island, as well as the Hatteras Inlet, a channel between Hatteras Island and Ocracoke Island.

However, sometimes you may see or hear reference to Cape Hatteras, which is in Buxton. The word Cape is a geographical term that refers to a large headland extending into a body of water, usually the sea. In the case of Cape Hatteras, if you look at the map, it’s that protruding area of Buxton village on Hatteras Island. The area was once called the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” for its treacherous currents, shoals, and storms where hundreds if not thousands of ships have been lost to the Atlantic. That is why back in 1803, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was erected there to warn approaching ships. The 3rd and latest version is still there so you, too, can visit it.

That makes Cape Hatteras rich in history and legends relating to shipwrecks, lighthouses, and the US Lifesaving Service, the predecessor to the U.S. Coast Guard. Also, let’s not forget the historic and best preserved jewel of Hatteras Island, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

However, the usage of the name Hatteras is not over yet. Then there is Cape Hatteras National Seashore, a United States national seashore which preserves a portion of the OBX. It starts in Bodie Island on the north and goes south down to Ocracoke Island, stretching over 70 miles. It’s managed by the National Park Service and Buxton’s shores are a part of it.

All dingbatters are welcome

Now that you know where the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is, even if you don’t ask where it is, it’s still time to reveal the meaning of the word “Dingbatter.”

Okay, here it is: While you are on the island, if you ask where the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is, then you are a Dingbatter. It is the islanders’ reference to you and me, outsiders. In other words, it is not a bad word and is a part of the unique Carolina Brogue of the Outer Banks Vocabulary. “Dit dot” or “Woodser” is also in the same category of words describing a person who’s not from the OBX.

For several centuries, the small villages dotting the barrier islands of North Carolina and the adjacent coastal mainland harbored one of the most distinctive varieties of English in the United States, the so-called “Outer Banks Brogue.” I must point out that Carolina Brogue and OBX Vocabulary is one of the most unique dialects in the world.

Buxton, surf fishing heaven on the East Coast

Most of the shores of OBX have ever-changing sand bars that aren’t too far from its shores, creating ideal fishing pools. Those fishing pools, especially on the shores of Buxton, become very productive shore fishing spots. Catching a 53” long drum fish while surf fishing would not be considered news in this town.

Some tourists catch and release the fish and others enjoy fresh catches on their tables. From May to September, Bluefish, Spot, Croaker, Sea Mullet, Flounder, Skate, Dogfish, Pompano, and Drum are the most common varieties of fish that are caught directly from the surf of the beaches. In the case of Hatteras Island, geography and nature have given a special gift to Buxton, making it a cut above ideal for surf fishing on its shores.

Buxton Woods, a gift of nature to Hatteras Island

If you look at the map quickly you would notice a huge green area, the Buxton Woods Coastal Reserve. It is a large, roughly 1,000-acre component of the North Carolina Coastal Reserve System that continues as Firesco Woods further down south to the Firesco village.

The site is located within the largest remaining contiguous tract of Maritime Evergreen Forest on the Atlantic coast. The Reserve also contains the only occurrence of a maritime shrub swamp (dogwood subtype) community in the world. Buxton Woods is a major source of groundwater recharge for Hatteras Island.

Buxton Woods occurs on a series of east-west running relic sand dunes. The seaward (southern) edge of the forest is a shrub thicket community dominated by live oak and red cedar. Further inland, the dune ridges are stabilized by a maritime evergreen forest. Visitors will be struck by the elevation and beautiful views from these ridges. I’m told that a good example of a remnant dune ridge can be found on the “Lookout Loop” trail off Old Doctor’s Road. Between the ridges, broad depressions support both seasonally and permanently flooded freshwater marshes, called “sedges.”

In the past, Buxton Woods was used for logging for shipbuilding. Local houses were often built using the shipwreck timbers hauled off the beach.

Buxton Woods serves as an important resting place for migratory birds in the fall. More than 360 species of birds have been recorded. Common mammals found in these woods include gray fox, mink, river otter, and white-tailed deer. Reptiles and amphibians found here include eastern box turtles, green anole lizards, and southern dusky salamanders. Two rare butterflies (northern hairstreak and giant swallowtail) are also found in the area.

It’s a local legend that Buxton Woods is home to a small handful of alligators, which have been reportedly spotted over the decades in local ponds, swampy regions, and even in residents’ wooded backyards.

Frisco and the Cora Tree – A halloween-worthy local legend

The North Carolina coast is home to countless tall tales, legends, and haunted stories to accompany its stunning and unique landscape of marshes, miles of beaches, and sometimes unforgiving storms. In the case of Frisco, it too has a legend, which would be perfectly fitting as a Halloween story. It is the legend of Cora.

The story goes back to the early 1700s of OBX. One day, a slight woman named Cora and her baby arrived in Frisco, where she had never been seen before. Because of a series of unfortunate events, she found herself in the center of a witch trial thanks to a man named Captain Eli Blood, a long-time native of Salem, Massachusetts. He determined that Cora was a witch and he knew just how to test her to prove that, being from Salem and a veteran of the Salem Witch Trials.

As the legend goes, Captain Blood tied Cora and the baby to a live old oak tree in the middle of town. After multiple back-to-back unusual events, lighting hit the spot where Cora and baby were tied. The oak tree was split in two from the power of the lightning bolt, she and the baby disappeared, and four letters, CORA, were burned so deep into the tree that they are still clearly visible today. Yes, to this date. Given that the oak trees in the US can live hundreds, if not thousands, of years, who knows, maybe that tree really witnessed such an event. In either case, when we visit Hatteras Island we intend to stop by and see the tree for ourselves.

I must tell you that my retelling of the legend here in no way does justice to this fascinating story. I highly recommend that you read it as Sara Gannon, the Island Free Press feature writer explains it.

Here is a little tidbit for you. All six miles of Frisco’s beaches are part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. Visitors with four-wheel drive vehicles are permitted to drive on specified Frisco beaches if willing to abide by the rules.

The village is also home to an extension of maritime forest that I talked about above while talking about Buxton, the village just north of Frisco. The forest goes mostly unnoticed due to the competing beauty of pristine oceanfront beaches just yards away.

Today, modern-day vacationers can enjoy the same landscape as the Native Americans, the original residents, enjoyed hundreds of years before with miles of thick forests, brushy marshlands, and small fresh and saltwater ponds sprinkled throughout rustic trails. Just don’t forget to visit the Frisco Native American Museum.

Hatteras

Well, we are on our last stop on Hatteras Island. We have reached the village of Hatteras at the most southern tip of the island. Well known for fishing, Hatteras is the microcosm of everything the Outer Banks has to offer, whether it’s beautifully pristine beaches, watersports on the sound, or fantastic fishing. The family-friendly, laid-back atmosphere of the village makes it a one-of-a-kind coastal jewel. Every September, the village hosts an Invitational Surf Fishing Tournament, with over 90 teams competing. The shores of Hatteras, just like the rest of the island, are approximately where the Atlantic’s cold water Labrador Current collides with the warm-water Gulf Stream, resulting in some of the largest waves available on the East Coast.

However, on the west side of the village, the Pamlico Sound offers calmer waters with plenty of water activities for tourists. The focus of Hatteras village is Hatteras Landing, a waterfront complex on the Sound offering shops, restaurants, live music, and a self-service marina. Where Road 12 ends at the end of the island, you will spot the Hatteras-Ocracoke Ferry terminal where visitors will find bicycle and moped rentals, fishing charter boats, and great sunset views.

Hatteras Maritime Museum, a.k.a. Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum, is an interesting spot. It’s well worth visiting, especially if you are a boater, as we are, or interested in the local culture where life has always been focused on the water.

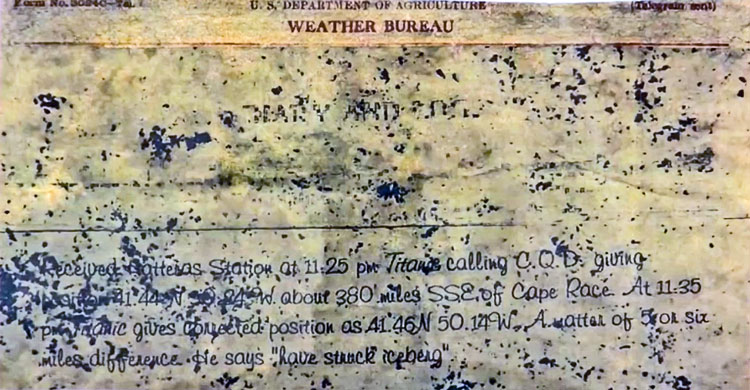

Among its often unique artifacts, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum has an actual telegram received by Richard Daily, supervisor on duty at the Hatteras Island Weather Bureau Station, recorded on the night of April 14, 1912, at 11:25 pm from the sinking ship Titanic, sending out a CQD message (today’s SOS). The story behind it is an interesting one that you can learn more about at the museum video link above.

Hatteras Inlet is the very dynamic waterway between Hatteras Island and Ocracoke Island. The Hatteras-Ocracoke Ferry connects both islands, but it wasn’t always there because the Inlet wasn’t always there. It was created in 1846 when a hurricane severed a semi-permanent strip of beach connecting Hatteras to Ocracoke Island, introducing a new permanent waterway. Some years, a series of storms have clogged the channel between Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands, making the channel impassable and forcing ferries to do detours.

Well, that’s it for now. Stay well. I hope to say hello to you if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK, in one of the locations that I’m hoping to visit in 2022, that is, if whatever the latest version of Coronavirus permits us.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Cover Photo: Hatters, OBX, North Carolina. Courtesy of North Carolina Maritime Museum, Hatteras a.k.a Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum.

5 things I learned

- If you visit Hatteras Island off-season during the colder months, such as January or February, and if you are very, very lucky, you may be rewarded by spotting a rare visitor, the snowy owl. They migrate all the way from near the North Pole, and can be seen on the beach between Frisco and Hatteras.

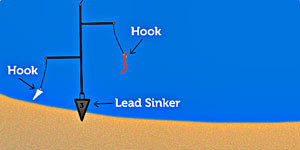

- Surf fishing is an interesting way of catching fish in OBX.

[Insert diagram; Diagram is courtesy of Southern Shores Realty ]

- In Morse Code, “SOS” is a signal sequence of three dots, three dashes, and another three dots, spelling “S-O-S.” The expression “Save Our Ship” was probably coined by sailors to signal for help from a vessel in distress. In earlier days, CQD originated by combining CQ, which alerted stations that a message was incoming, with D for “distress.” To learn more about the CQD message and today’s SOS, check this link.

- If you want to visit Buxton Woods Coastal Reserve, you can find more information and a Buxton Woods map here.

- Map of off-road vehicl access

1 thing I recommend

- There is something for everyone and every age, and a lot to do on Hatteras Island. Select your preference among the extensive visitor activities in Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Just start planning.

How easy?

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned or Planning to visit,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL. The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current, and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present. My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?