The Alligator River, a ghost town and moonshine capital, and Belhaven, NC on the ICW

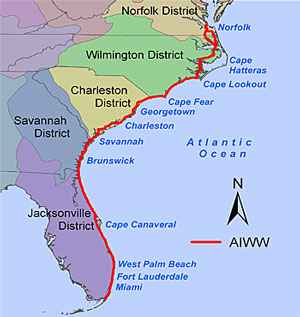

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes – SBFL 23* – PLANNING TO VISIT – I am writing this series, Slow Boat to Florida, because through others’ experiences we can learn something that could help us prepare for things that we might otherwise have overlooked during our journey on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW). It is also a way to discover some wonderful stories. Right now, I’m reading a passage from a book that paints an unusual story of a fascinating encounter. “Down the waterfront, I had glimpsed a ship with four tall masts, and I walked along the shores until I found her alongside an old bulkhead. Soon I stood on the deck of the most bizarre ship I have ever seen and talked to one of the most singular men I have ever encountered.

“The W. J. Eckert was an ugly duckling. Stain and rust spotted her unpainted metal hull. Oil drums cut in half and fitted into the deck served as hatches. The rough wooden masts looked as if they had been hewn with stone axes. The ship had no yard-arms or running rigging. Though 98 feet long, she had a beam of only 14 feet—no wider than Andromeda—so that she seemed skinny as a fence rail. When the wind gusted to about 15 knots, I could feel her heel over.” These are the words of author Allan C. Fisher, Jr., (one of our two inspirational boaters) in his 1973 book published by National Geographic titled, America’s Inland Waterway (ICW). These are the kinds of stories that drive us to look over the horizon.

The essence of our Slow Boat to Florida series is you, our readers, ICW travelers, ICW gypsies, and the history of today’s ICW. That is why we have taken the original “Slow Boat to Florida” article written by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in January 1958 and the 1973 book America’s Inland Waterway (ICW), both published by National Geographic, and are following the authors’ route to have our own experiences along the same route.

I want to explore and enjoy what the ICW environment offers us. We prefer not to treat the ICW as if it was a major highway, such as Route 95 on the US East coast, and zip down to Florida. To us, the ICW is not a major highway. I feel that if we get into a frame of mind to just reach Florida in a hurry, we will miss too many towns and history on the shores where the Unites States of America started.

So here we are. I started planning our version of the Slow Boat to Florida journey and started writing about our plans in 2018. Then the Covid pandemic made us miss our start date of October 2020. Now we are in 2022, still planning. If you want to see what we have posted so far, check out the “Stories You May Have Missed” section of our site and select “Slow Boat to Florida (SBFL) Series” on the dropdown menu.

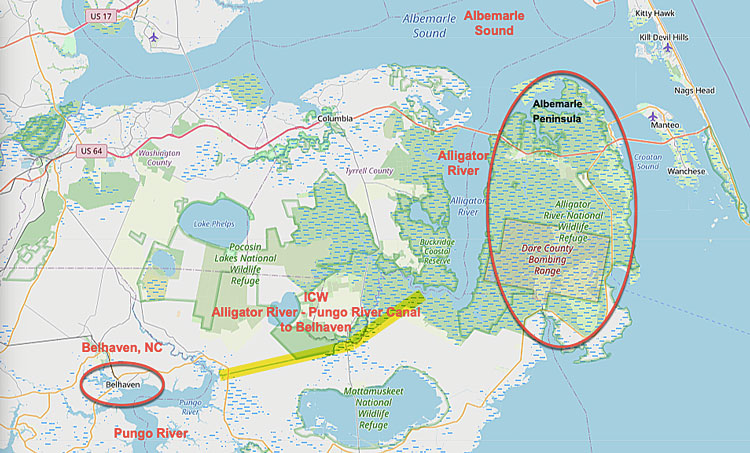

In our previous post on the Slow Boat to Florida series, we crossed the Albemarle Sound going south on the ICW, heading to the Alligator River.

Alligators of the Alligator River

Most of us may think the Alligator River is named for its inhabitants, alligators. However, apparently, it’s named for its shape. Still, don’t make the mistake of thinking there are no alligators. The area is home to the American Alligator, which inhabit areas north of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and in some of the waterways.

You can see alligators in the Alligator River, Milltail Creek, Sawyer Lake, and in the border canals that line Highway 64/264 in Manns Harbor and Stumpy Point. The American alligator ranges throughout the southeastern United States. Adult male alligators occasionally reach 13 to 15 feet in length. The maximum length for females is approximately 10 feet. The snout of an alligator is characteristically broad, although the shape can vary slightly among populations and individuals.

Buffalo City, a forgotten ghost town of the Albemarle Peninsula

In 1973, referring to their Alligator River passage, Fisher wrote, “in the Alligator River we sailed protected waters, with cypress swamps on either side and not a sign of habitation.” They were surprised and happy to see how much of the ICW remained as wilderness.

Today, boaters on the ICW passing through the Alligator River may still enjoy the natural look of its shores. This is especially true for the eastern part of the river of this huge Albemarle Peninsula, named the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

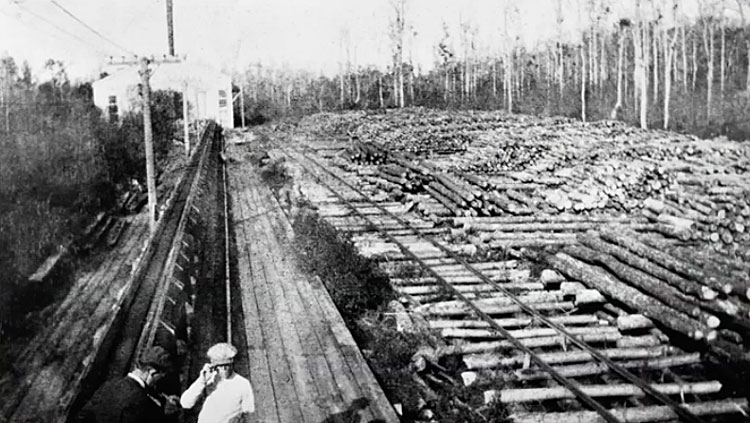

However, the wilderness that you may observe has a different past. This story of the peninsula started on Sept 7, 1795, when John Gray Blount purchased an estimated 100,000 acres of land, a.k.a the Blount Patent, which was almost the entire peninsula. Today that area, plus a bit more, is known as the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. The land was under private ownership for 188 years, and multiple owners formed multiple lumber companies. Buffalo City, today’s forgotten ghost town, was born as a logging company town, and 800-1,500 Russian immigrants and African American enslaved people worked and lived there with their families. Later it became the moonshine capital of the US.

In the 1850s, Buffalo, New York, developed a substantial lumber trade. In 1888, businessmen Frank and Charles Goodyear bought large tracts belonging to the Blount Patent of isolated forests near water transportation. There they built sawmills and Buffalo City. They connected it to shipping centers by waterways and railroads. The newly formed Buffalo Timber Company brought its own labor force, which included Russian immigrants and African American enslaved people. According to many, however, these racial distinctions hardly mattered at the time. Even now, more than half a century later, former residents and their descendants still gather every September for an annual “Homecoming” that celebrates the vanished town just 19 miles west of Manteo, an Outer Banks town. They built the village in the middle of the wilderness without electricity and plumbing by hand. Rows of identical structures were divided by a railroad spur down the middle. Residents endured seasonal extremes and wildlife, including virulent insects, alligators, and bears.

Meanwhile, between 1880 and 1920, thanks to the Dismal Swamp Canal, which today we use as one of the ICW routes, over 40 forest companies were established in Elizabeth City. They made a variety of wood products. At the time, Elizabeth City became the leading lumber export port in North Carolina.

By 1911, all the trees on the north side of the Albemarle Peninsula were cut. The rest of the trees were on the south side. Buffalo Timber Company, the town’s employer, having depleted most of the trees of the northern part of the peninsula, moved to Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

Moonshine capital of the US

As quality timber became increasingly scarce, residents began producing bootlegged moonshine to sustain their very modest life. Logging and bootlegging overlapped. During both pre-and post-date Prohibition, Buffalo City’s finest became very famous.

Telling the story, the North Beach Sun wrote, “It wasn’t your run-of-the-mill homemade whiskey either; this was the good stuff. Though Buffalo City manufacturers made some whiskey with corn, it was their smoother rye version that put them on the map. Known more generally as East Lake whiskey, demand was high for this carefully crafted liquor, particularly in big cities such as Washington, D.C., and New York. Some speakeasies were rumored to have kept specially branded East Lake whiskey cocktails on their menus, while other rival distributors were said to have slapped fake East Lake labels on their bottles in order to improve sales.”

Birth of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge

For 188 years, the various business efforts persisted in the peninsula. Then in 1983, the Prudential Life Insurance Company, the financial underwriter of the First Colony Farm Company, the final commercial entity on the Blount Patent, ended up taking ownership of the land. They gifted it to the U.S. government as a tax write-off.

Today, Buffalo City, the ghost town, is part of the 152,000-acre Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

Alligator River passage to Belhaven on the ICW

Our other inspiration source is Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones, and their 1958 National Geographic essay titled, “Slow Boat to Florida.” After crossing the Albemarle Sound, they felt the next stop, Belhaven, was beyond their reach of a day’s run. They sheltered midway at an Army Engineers maintenance wharf in a side canal near the Highway 94 bridge.

They walked up and struck up a conversation with the bridge tender. The topic was mosquitoes. The man said, “Mosquitoes? Not bad yet, but in another month, they’ll like to eat a man up.”

Oh yes, those nerve-twisting, bold, sucking, nasty bugs, mosquitoes that can ruin our day or night. I believe that every living being in this world may have a purpose. However, I can’t figure out what in the world is the purpose of mosquitoes. Whether there is a purpose for them or not, plan to encounter mosquitoes during most of your ICW trip, full stop. Every bug, size, and quantity is waiting for us to be served to them by no other than ourselves. In short, we all have to prepare and expect to have them along the ICW. We, too, expect to encounter them, ambushing us in groups of the squad, platoon, and who knows, perhaps battalion size.

Belhaven, North Carolina

The Jones’ in 1958 referred to Belhaven saying, “Everybody we met along the waterway spoke warmly of Belhaven as a stopping place and upon arrival there we quickly learned why. A jovial Tarheel named Axson Smith has turned a roomy old mansion into River Forest Manor. And dedicated it to the care and feeding of water-borne travelers.”

Axson told them stories about the visitors he was least likely to forget. Apparently, one couple cruised all the way from Long Island, New York to North Carolina without spending a cent for fuel, nor did they have sails. The boat was a government surplus. It was a converted landing craft fitted with a cabin. As the story goes, Axson explained, “The owners, a man and his wife, would get a tow from the harbor to the nearest channel. Then they’d sit and wait. A yacht would come along and they’d yell, ‘My engine is out! Well, yachtsmen are kind-hearted, and the first thing you knew this old bucket would move along at the end of a towline to the next port. One day a real Samaritan came along. He insisted on going below to fix the engine. He lifted the engine-room hatch. The engine really was ‘out.’ There wasn’t any.”

Today, on ICW mile marker 136 (35° 31.916 North, 76° 36.858 West) the stately establishment that Axson Smith built-in 1904 is called River Forest Manor & Marina. The marina is worth a stop and is located near many restaurants and attractions.

The marina’s pier features a renovated main pier and a new secondary pier. The marina has more than 375 feet of dockage for watercraft of up to 150 feet.

Although Axson Smith’s family closed the hotel in 2011 and sold it in 2014, the family is still around with their third generation, Axson Smith III. Captain Axson Smith, Jr. has been in the marine business for more than 40 years and has run TowBoat US River Forest since 1993 and owns River Forest Boatyard/Shipyard.

Back in 1973, Fisher referred only to “Belhaven in a little harbor huddling behind a low and inadequate breakwater.” That was his only reference to Belhaven. It seems that a lot has changed since then. It’ll be interesting to see what it’s like now, when we finally get there.

Well, that’s it for now. Stay well. I hope to say hello to you if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK, in one of the locations that I’m hoping to visit in 2022, that is, if whatever the latest version of Coronavirus permits us.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Cover photo: Main building of River Forest Manor & Marina. Photo courtesy of River Forest Manor & Marina

A few things I learned

- On the mainland of Dare County, North Carolina all that remains is some railroad track and a few old bricks, from what once was a logging town with over a thousand residents, their homes, a general store, a school, a church, and a lumber mill. Before it disappeared in into the forest, it also became known as the moonshine capitol of North Carolina.

- Former Moonshiner Cookie Wood Talks Moonshine & Bootlegging

If you see an alligator – Safety tips

- Space: Respect an alligator’s space and stay back at least 20-30 feet. If you get too close, back away slowly. Alligators are actually extremely quick and agile

- Hiss: If an alligator hisses, it’s warning you that you are too close. Back away slowly.

- Pets: Pets are the size and shape of common alligator prey. Keep them away from the water’s edge and on leashes that are no longer than 6 feet. Do not let your pet drink from or enter the water in the alligator habitat.

- Feeding: Never feed wildlife that you encounter, including birds. Feeding wildlife of any kind will eventually make the animal aggressive and is illegal.

4 things I recommend

Marina’s to stay:

- Town Dock in 2011. Belhaven Marina ICW at Mile Marker 136

- River Forest Manor & Marina ICW at Mile Marker 136

- Downy Creek Marina ICW at Mile Marker 131.5

Also check out:

How easy?

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned or Planning to visit,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL.

The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish.

The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present.

My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?