What happened at Roanoke Island?

OBX, where coastal legends are born – Part 2 – Roanoke Island

… Estimated reading time: 10 minutes – SBFL 16* – PLANNING TO VISIT – We are continuing to follow the footsteps of Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida,” (SBFL), and the 1973 book of Allan C. Fisher, Jr., published by National Geographic, titled, “America’s Inland Waterway.” In our previous post, in Part 1, we planned to leave our boat, Life’s AOK, in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, and do a multi-day excursion to the Outer Banks (OBX) on the path of the Jones’. As per Fisher’s notes, he did not stop by the Outer Banks. From Elizabeth City, he headed straight to cross the notorious Albemarle Sound.

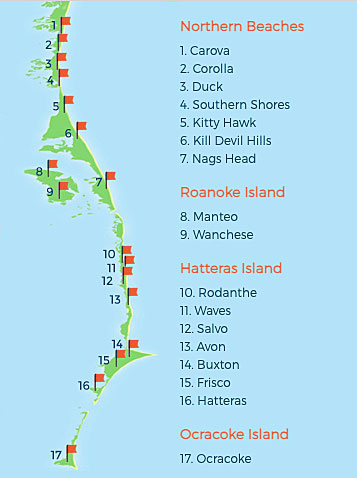

For now, we are continuing to follow the footsteps of the Jones’ taken back in 1958. It seems that now in 2021 some things have changed a lot in the Outer Banks, while some other parts still remain the same, perhaps for thousands of years as in the case of its sandy islands facing the Atlantic Ocean and its ever-changing winds. Our OBX excursion will take us the full length of the 320-mile island chain over land. Then we will drive back to Elizabeth City and meet up with Life’s AOK to press forward.

Once again, we will crank up our virtual Way-Back-Then-Machine, the time capsule generator. When we actually visit our planned excursion spots, it will help us to compare each place through the eyes of the Jones’ back then, as well as the people who love to call their coastal communities home now, in the 21st century.

In Part 1 of OBX, Where Coastal Legends Are Born, we covered the Northern Beaches of the Outer Banks. Now it’s time to visit Roanoke Island, located in the middle of the island chain.

Roanoke Island, what happened to the Lost Colony?

Well, the Jones’ did not visit Roanoke Island back in 1958 but we plan to stop on the island and visit the town of Manteo, as well as Wanchese. It appears that there have been a lot of changes since 1958 on the island.

Our Roanoke Island story starts in the 1500s with Sir Walter Raleigh.

He made an attempt to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. He was an English soldier, explorer, poet, and courtier who funded three voyages to Roanoke Island (1584–1587) and whose ostentatious manner of dress and love for Queen Elizabeth became legendary.

The colonists of the first expedition arrived at Roanoke Island on June 26, 1585. Thomas Hariot and expedition artist John White explored and mapped the area around Roanoke, carrying out Raleigh’s request that they present him with both textual and visual depictions of the settlement and its surroundings.

John White was an English artist accompanying the first failed colonizing expedition to Roanoke Island. White produced watercolor portraits of Virginia Indians and scenes of their lives and activities. He rendered the local flora and fauna and, using the English polymath Thomas Hariot as a surveyor, created detailed maps of the North American coastline. The first attempt to colonize, known as The Military Colony, failed due to food and supply shortages and conflict among the expedition leadership.

A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, by Hariot, was the first book about North America to be produced by an Englishman who had actually visited the continent. First published in 1588, Hariot’s report documented his trip to Roanoke Island off the Outer Banks from 1585 to 1586. A briefe and true report came to be one of the most important texts produced in relation to the beginnings of English settlement in the Americas. Containing engravings of images by John White, played a crucial role in encouraging English investors to continue their colonial endeavors in the New World and thus led directly to the beginnings of English settlement in Virginia.

White, in 1587, served as governor of a second failed expedition, which came to be known as the Lost Colony. The second expedition was intended for Virginia, but due to leadership conflict, it ended up at the exact location of the first expedition, Roanoke Island. The legend of Roanoke Island has been passed down from generation to generation since 1590 when the second expedition group mysteriously vanished. White, the leader of the colony, went to England to get more supplies. When he returned in 1590, the settlement was deserted. All the settlers had mysteriously disappeared. The only clue he found was the word “Croatoan” carved in a tree. To this day, no one knows what happened to them. It’s possible that the Colonists joined with the friendly Croatoan natives. Or they were massacred by the unfriendly Wanchese tribe. No one knows for sure. Since 1937, this mystery has been relived every year in a play called The Lost Colony. It is performed outdoors at Waterside Theatre at Fort Raleigh in North Carolina. Speculation that they had assimilated with nearby Native American communities appears in writings as early as 1605. Investigations by the Jamestown colonists produced reports that the Roanoke settlers had been massacred, as well as stories of people with European features in Native American villages, but no hard evidence was produced.

An article titled, “‘The mystery is over’: Researchers say they know what happened to ‘Lost Colony’ “ published in the Virginian Pilot newspaper in August 2020 sheds some light as to what happened to the lost colony. Spoiler alert! “The English colonists who settled the so-called Lost Colony before disappearing from history simply went to live with their native friends — the Croatoans of Hatteras, according to a new book.” Well, maybe they did, maybe they didn’t, who knows.

Before we cross to Hatteras Island

The gorgeous beaches, sand dunes, wide-open spaces, and wind take center stage on the Northern Beaches of the Outer Banks that we talked about in Part 1 of this series. On Roanoke Island, the stage belongs to a deep and very interesting history of the birthplace of English colonization in America (literally).

Two quaint villages of the island that we plan to visit are Manteo (you can drop the t and pronounce Manteo as Maneo just like locals do), and the major fishing village of Wanchese, each having a population of nearly 2,000 people.

Manteo or Maneo, it is okay to pronounce either way

So, now that we are in 2021’s Roanoke Island, we plan to visit a few spots and enjoy mingling with the locals. Some of the spots that we plan to visit were there long before the Jones’ 1958 visit, as in the case of Roanoke Island in the 1500s or Bodie Island Lighthouse, initially built in 1837 and rebuilt few more times since then.

Other spots were much newer, including the then newly-built Elizabethan Gardens in Manteo that were founded in 1951, or came well after the Jones, such as Roanoke Island Festival Park, the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island, Roanoke Island Maritime Museum, or Fort Raleigh National Historic Site that is known as England’s First Home in the New World. Along the way, we’ll also explore the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, with its 154,000 acres of wetland habitats and a wide variety of wildlife, ranging from wood ducks and alligators to black bears and red wolves, and its warmly welcoming National Wildlife Refuges Visitor Center.

Now let’s crank up our virtual Way-Back-Then-Machine, the time capsule generator, and open it up to see the Bodie Island Lighthouse story. Back in 1837, the U.S. federal government sent Lieutenant Napoleon L. Coste of the revenue cutter Campbell to examine the coastline for potential lighthouse sites that would supplement the existing one at Cape Hatteras.

The Bodie Island Lighthouse was first built in 1847, but then later had to be abandoned within just a couple of years. The brick foundation was unsupported, causing the tower to lean and making subsequent repair attempts unsuccessful and incredibly expensive. The second lighthouse, built nearby, was built in 1859. However, it was destroyed in 1861 by retreating Confederate troops who feared that the lighthouse, which was 156 feet high, would be used as a Union observation post during the Civil War. Then, the third and current lighthouse was built in 1872. It was distinguished by having its original Fresnel lens. Today, the lighthouse has thankfully been restored to avoid further punishment of time and mother nature for all to enjoy. It was reopened to the public in 2013. Well, where is the Bodie Island Lighthouse? It is located just south of Nags Head, and is approximately 7 miles south of Whalebone Junction, which is the intersection of US 64, US 158, and NC Highway 12.

Wanchese, the seafood capital of the Outer Banks

Then comes the fishing town of Wanchese. It is a true fishing village. Historians believe that the town is, in fact, the first fishing village of the Outer Banks, as local Native Americans dating back to 900 A.D. settled there and made treks either by boat or along the shoreline to reel in the bounty of the Roanoke Sound. In fact, the town name of “Wanchese” is in honor of the Roanoke Tribe’s chief, who in 1584 accompanied the neighboring Chief Manteo on an expedition to England, but returned home the next year somewhat disenchanted with the new European arrivals. Some theorists postulate that it was Chief Wanchese’s aggression that sealed the fate of the infamous Lost Colony settlers in Manteo.

Today, the village is home to the North Carolina Seafood Industrial Park as well as smaller waterman businesses. There, commercial vessels and seafood dealers of all kinds congregate to sort through the day’s catch and provide fresh North Carolina seafood for virtually all of the Eastern Seaboard. That is not a small feat. Also, marinas in the town serve as a launching point for shrimp trawlers, flounder boats, and other huge vessels that travel out to the Gulf Stream and beyond for weeks at a time in search of large hauls to be brought home.

The town also is a home for the watermen who make their living with Wanchese soft crabs and other seafood. Most of the fresh seafood that winds up on the Wanchese docks ends up on the plates of Outer Banks restaurant patrons several days, if not hours, later.

If you are a serious offshore fishing lover or want to try it once, Wanchese is the place to be.

Next, it’s time for us to get back to the Jones’ route and plan for our next stop, Hatteras Island. After the Northern Beaches, the Jones’ skipped Roanoke Island and crossed Oregon Inlet (Part 3) on a ferry boat with fishermen and vacationers. That is the Hatteras Island destination in the southern part of the Outer Banks. Our plans for that will be in our post, “OBX, where coastal legends are born—Part 4.”

Well, that’s it for now. Stay well. I hope to say hello to you if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK, in one of the locations that I’m hoping to visit in 2022, that is, if Coronavirus permits us.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Cover photo: The Bodie Island Lighthouse, Outer Banks, North Carolina. Photo by Michael Ver Sprill (OBX)

2 things I learned

- Ships of the Historic Roanoke Voyages

- Have you seen commercial fishing on a large scale?

1 thing I recommend

- For those who may visit Roanoke Island by boat, watch the below video

How easy?

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned or Planning to visit,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL. The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present. My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?