The Legend of the Oregon Inlet

OBX, where coastal legends are born – Part 3 – Oregon Inlet

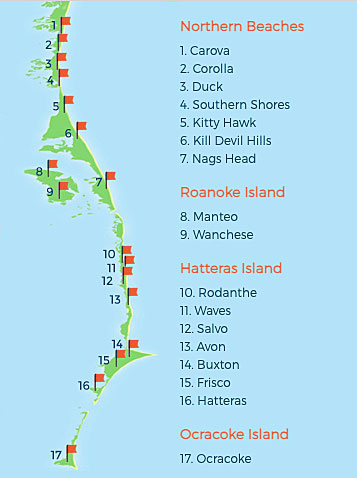

… Estimated reading time: 9 minutes – SBFL 17* – PLANNING TO VISIT – Honestly, when was the last time you thought that the waterway under you as you were crossing a bridge might have a history, let alone a legend, associated with it? Welcome to the Outer Banks (OBX) of North Carolina. Almost every significant spot that you may stand on or pass by on the OBX has a legend. Well, the waterway, the Oregon Inlet, that we will be crossing using a great 2.8 mile-long bridge to Hatteras Island, has a legend as well. In Part 2 of this OBX mini segment, we talked about Roanoke Island. Now we are planning to continue southward along the 320-mile long stretch of the OBX, crossing from Roanoke Island to Hatteras Island.

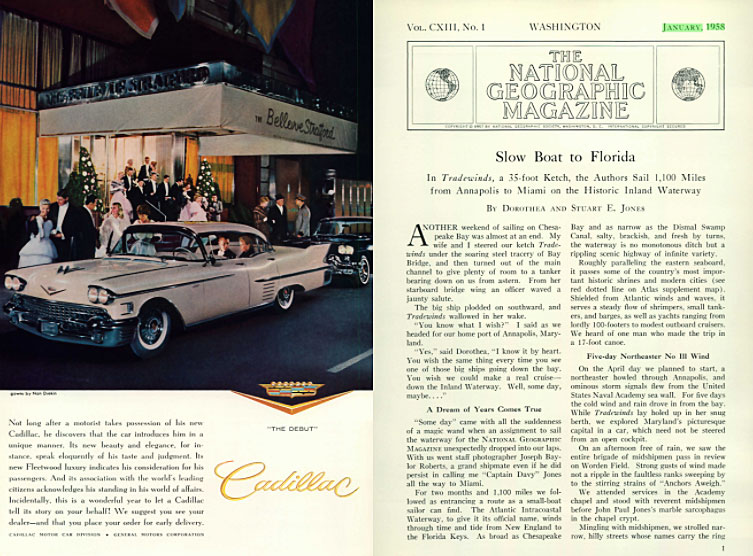

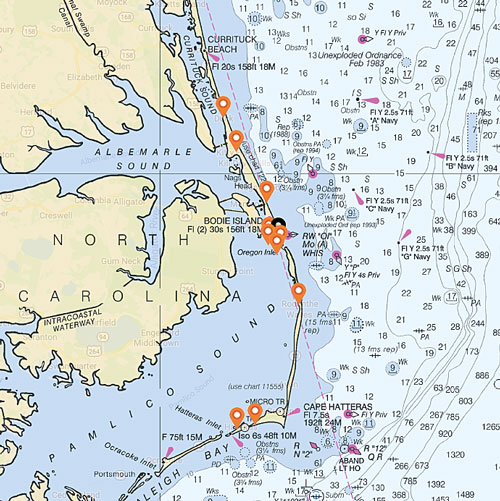

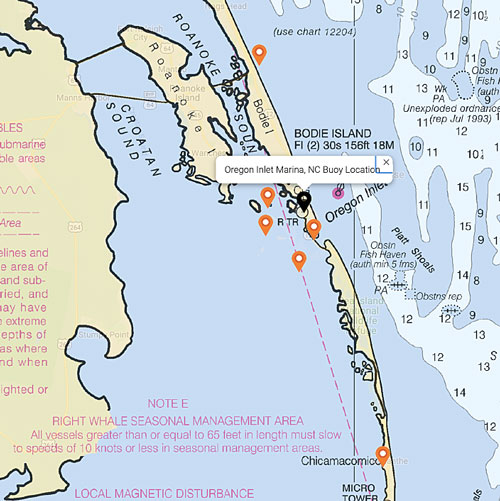

The Oregon Inlet is located just south of Nags Head, and separates Hatteras Island to the south from Bodie Island and the rest of the central Outer Banks to the north. It is 2.5 miles wide, which makes it one of the widest inlets on the OBX. As our avid readers would recall, in this Slow Boat to Florida (SBFS) series we are following the sailing route of two separate National Geographic editors, our inspiration for our boat trip planning. In the case of our OBX visit, we are tracing the footsteps of Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida.”

Now, let’s crank up our virtual Way-Back-Then-Machine, the time capsule generator. Back then, the Jones’ crossed Oregon Inlet on a ferry boat with fishermen and vacationers. Today in 2021, there is no ferry to hop on for us. Instead, on North Carolina Route 12, there is a 2.8-mile long bridge to take us to Cape Hatteras. However, a small handful of islands on the Outer Banks, specifically Knotts Island, Ocracoke Island and Portsmouth Island, are relatively cut off from the rest of the world. With no roads that cross over the Currituck or Pamlico Sound, these regions can only be accessed by boat, making them dependent on the North Carolina Ferry System for transportation on and off the islands.

Walking waterway

Okay, I personally find this amazing! Oregon Inlet, akin to many other inlets along the OBX, moves southward due to drifting sands during tides and storms. It has moved south over two miles since 1846, averaging around 66 feet per year. Talk about a walking waterway!

The legend of the Oregon Inlet and its birth dates back to September 1846, on a night when a hurricane shook that area of the ocean known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic Ocean. A small trading ship named Oregon was making a return voyage to Edenton, North Carolina from Bermuda. On the last day of their journey, the winds kicked up and the skies turned dark. It was soon obvious that a hurricane was coming, and the ship was in danger. The ship struggled to reach the safety of port before the storm struck. However, it was too late—the hurricane caught up with Oregon and the small ship was tossed by the increasingly violent waves.

According to the legend, “Suddenly, a tremendous surge came in from the sea. The boat was lifted high into the air, and the crew felt the deck tilting beneath them. They feared all was lost, but suddenly the rocking stopped. Though still pounded by the wind, the ship was no longer being moved by the waves. The crew were astounded. They realized that the enormous wave had picked up the Oregon and deposited her on a sandbar. Amazed at their luck, the crew thankfully rode out the night sitting safely above the tumultuous sea. The next morning, the crew discovered that the hurricane had done more than just save their ship. Beside the sandbar where the Oregon now sat was a wide channel. Consulting their charts, they were able to determine their location and realized that this inlet wasn’t on any of their maps. The huge wave that had raised up the Oregon to safety had, at the same time, forced open this new passage in the Outer Banks. The Oregon had been the first ship to travel through it, only seconds after the inlet had come into being. When the Oregon arrived back at port in Edenton, they let the town know of the new passage. Soon, the channel became one of the most important passages through the Outer Banks, and in honor of the first ship and first crew to pass through, it was named the Oregon Inlet.”

Random tidbit: By the way, the State of Oregon on the West coast of the US, was established 13 years after Oregon Inlet formed.

Oregon Inlet changes the life of OBX

The Oregon Inlet is famous for igniting the North Carolina Ferry System that serves the coastal islands of the Outer Banks. In the late 1830s, a decade before the Inlet was formed, Hatteras Island was already home to a healthy population of tradesmen, lifesaving station employees, and local villagers. Hatteras Inlet had also opened up at the southern end of the island, just south of Hatteras Village. The population was essentially stranded, and the only way to get on or off the island was by boat. During the 1850s and beyond, this wasn’t necessarily a concern since with no roads or vehicles, a boat was the only logical method of transport.

However, later as the times passed and changed drastically, the Hatteras Islanders wanted to visit the southern Outer Banks and needed a way to get across Oregon Inlet. An enterprising local, Captain Toby Tillet, took care of the need in the 1920s. He began to make ferry runs across Oregon Inlet with a tugboat and barge that could carry a small number of vehicles across the water. By 1950, Tillet’s entire ferry business was sold to the state, and soon other state-sponsored ferry operations began to pop up along the Outer Banks, most notably across the Croatan Sound, which became the first official North Carolina Ferry route.

Apparently by the late 1950s, the ferry traffic to and from Hatteras Island had increased to the point that a bridge was necessary, and the Herbert C. Bonner Bridge officially opened to vehicles in 1962, spanning across Oregon Inlet, and providing commuters and day trippers with an easy way on and off the island.

Bonner Bridge over the inlet

While most visitors think of the Bonner Bridge as a means to get to their final Hatteras or Ocracoke Island destination, the Bonner Bridge is, in fact, an attraction all its own.

The bridge, with mile-wide views and a legacy of bringing mass tourism to the island in the first place, is an essential part of the cultural make-up of Hatteras Island. Today you can stay a while and discover the sheer beauty of the Bonner Bridge, both from the top of the span, and from the bordering beaches or bridge walkway. You can spend a little time admiring the view from different perspectives, and you’ll surely gain an even greater appreciation of Hatteras Island’s waterfront vistas at their finest.

Located close to the Gulf Stream for exceptional offshore fishing, Oregon Inlet is a popular waterway for commercial and charter fishermen alike, who make daily runs under the Bonner Bridge to the open ocean waters. The most popular activity along the perimeter of Oregon Inlet is fishing, as in all Outer Banks inlets. Deep sea fishermen and surf fishermen alike will find plenty to love about this area. Many of the charter boat businesses on the Outer Banks pass through Oregon Inlet to get to the Gulf Stream, particularly all of the businesses that cater to the central Outer Banks regions. Oregon Inlet Marina, which is literally located on the northern banks of the inlet’s borders is one of the best spots to catch fishing boats. Making fishing trips from this marina is one of the quickest runs out of the sound and into the open ocean waters.

In recent years, Oregon Inlet has become a point of controversy. Because of the nature of inlets, which are continuously expanding or retracting, the inlet has begun to close up and efforts have been made by the state and federal governments to commence regular dredging to keep the inlet wide open for commercial and charter fishermen. That is the point where the controversy starts. For some, this costly endeavor may simply be delaying the inevitable closing of the inlet. Others insist that efforts are necessary to keep the local fishing industry intact. Annual dredging efforts are still underway, and visitors passing over the inlet on the Bonner Bridge may spot huge dredging ships, spouting tons of sand and water into the air above.

In our next post, Part 4, after crossing the Bonner Bridge we will be planning to visit Hatteras Island. Its Cape Hatteras Lighthouse still protects one of the most hazardous sections of the Atlantic Coast. Offshore of Cape Hatteras, the Gulf Stream collides with the Virginia Drift, a branch of the Labrador Current from Canada. This current forces southbound ships into a dangerous twelve-mile-long sandbar called Diamond Shoals. Hundreds and possibly thousands of shipwrecks in this area have given it the reputation as the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

Well, that’s it for now. Stay well. I hope to say hello to you if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK, in one of the locations that I’m hoping to visit in 2022, that is, if Coronavirus permits us.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Cover photo: Bonner Bridge, Outer Banks, North Carolina. Photo courtesy of Island Free Press

2 things I learned

- Bonner Bridge Pier opened on Oct. 1, 2021. The 1,046-foot-long remnant section of the Bonner Bridge, located next to the south end of the Basnight Bridge, is managed by Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The Bonner Bridge Pier is a great place to walk, sightsee, watch for marine life, and enjoy recreational fishing. The pier is free and open 24 hours a day.

- Cape Hatteras vessel groundings

1 thing I recommend

- Slow down and take it all in

How easy?

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned or Planning to visit,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL. The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present. My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?