It’s time to head South or is it?

Estimated reading time 15 minutes – SBFL 10* – PLANNED – “We had been home from northern waters only a few weeks when the first tinges of red and gold along Church Creek told us it was time to head south. As crew, in addition to Mike and Bill Gay, we signed aboard Mrs. Virginia Finnegan, an editorial assistant at the National Geographic Society and my close colleague for 21 years,” wrote Allan C. Fisher, Jr., in his book, America’s Inland Waterway.

So, what’s this quote about? As much as I have felt the same way, that it’s “time to head south” since mid-October, here we are, grounded on land due to the pandemic. We’ve had a few small day trips within the Maryland borders of the Chesapeake Bay, such as to Chestertown and Swan Creek. However, we’ve just been in planning mode for the rest of our Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) trip to Florida. Our avid readers may recall that we’re comparing the then and now of life on the water and land on the ICW, using observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic essay, “Slow Boat to Florida,” and the 1973 book published by National Geographic, cited above, America’s Inland Waterway by Allan C. Fisher, Jr.

Slow boat to Florida

The essence of our Slow Boat to Florida (SBFL) series here is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog, Trips Of Discovery) that comes from seeing what was always just over the horizon with a new eye. We also take a brief look at the rich history of the locations that I’m writing about. We are focusing on our observations on the shores of today’s ICW, where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life today in the 2020s. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents, which is great fun for us. We absolutely love and appreciate talking and spending time with local residents of the towns that we visit and sharing it with you here. We are planning on doing our visits with our boat, Life’s AOK; however, the good news is not every reader of our blog must have a boat. In other words, all the spots that we are planning to visit or have been to are accessible by land with any kind of vehicle. They all are coastal living spots after all.

So, before crossing the Chesapeake Bay waters from Maryland to Virginia for their Slow Boat to Florida essay, the National Geographic captains who have inspired us made a few visits on the western shores of the Bay. In 1958, Dorothea and Stuart Jones, along with National Geographic staff photographer Joseph Baylor Roberts, visited Baltimore, Annapolis (their home port), and Solomons with their boat Tradewinds. In 1973, Allan Fisher, Jr., with his boat Andromeda, stopped on both the eastern as well as western shores of the Maryland part of the Chesapeake Bay. He visited Swan Creek, Wye River, Annapolis, St. Michaels, Oxford, Solomons, Deal Island, Chrisfield, and Smith Island. On a fall day, he continued, headed down south on the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) on the way to Florida.

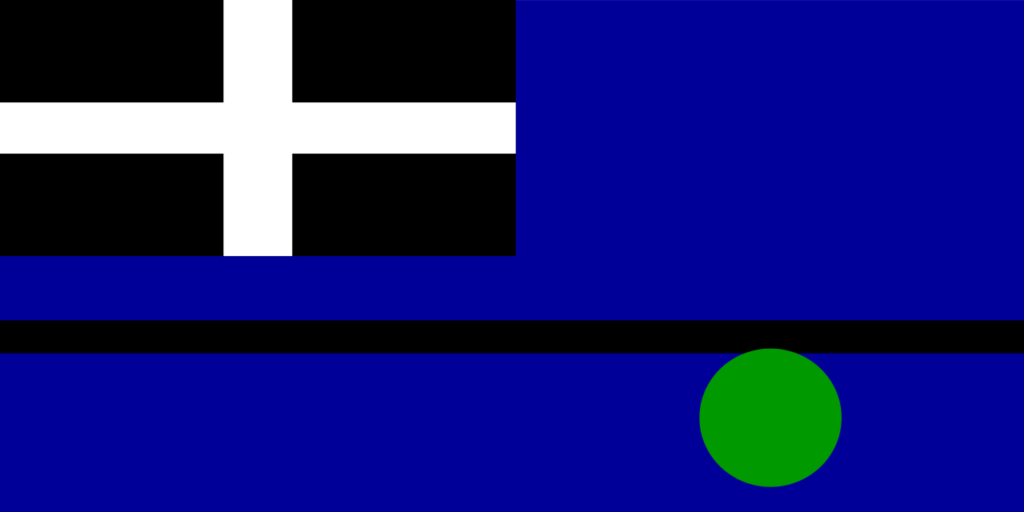

Flag of Smith Island, Maryland

Flag of Tangier Island, Virginia

Entering the Virginia waters of the Bay

Fisher, after visiting Smith Island on the Maryland side, went to neighboring Tangier Island, hence entering the waters of the Virginia part of the Chesapeake Bay. He planned to continue down to Hampton Roads and Portsmouth on the way to Florida’s warmer waters.

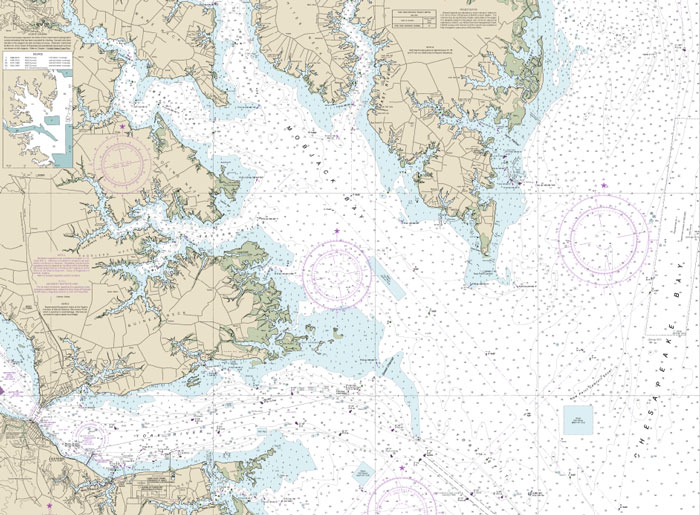

In the case of the Jones’, they left Solomons, Maryland, also heading down to the Hampton Roads area. After two exhausting days of heavy seas, they went through Mobjack Bay’s fish trap stakes, where heavy timbers that reached 20 or more feet to the bottom could easily open a hole in a boat. (Mobjack Bay lies between the Rappahannock River on the north and the York River on the south.) They finally reached the King-Robins Marina off the York River and spent a night in a brand-new motel in nearby Ordinary, an unincorporated community in Gloucester County, Virginia. The community was named after its local ordinary during colonial days.

In the colonies, like now, an inn was a commercial establishment providing, among other things, lodging and food for the public, particularly travelers. A “public house” was an inn or tavern that served the public. However, any inn or tavern that served a complete meal at a fixed price was referred to as an “ordinary.”

As a part of the King’s encouragement of commerce to grow in the colonies, the establishment of inns and public houses was legally defined under English law. Thereafter, the colonial courts required that some kind of public house be established in each community. Prices within these early American public houses were under the strict guardianship of the government. In the century or so leading up to the Revolution, colonial taverns and inns were an essential part of the community, serving a mix of clientele from all walks of life.

Pirates and privateers galore

During the colonial era and for some time after, the eastern seaboard of the United States became quite active grounds for pirates, as well as privateers (who were privately-owned armed ships, like pirates, but who were legally commissioned by their government to fight or harass enemy ships). While most famous pirates such as Stede Bonnet and Blackbeard were active in North Carolina, the Chesapeake Bay region developed quite a bit of history on that front as well. Thaddeus Fitzhugh was one of the well-known pirates of the day who led a very rich sacking of Cherrystone in Virginia. Today, Cherrystone is an unincorporated community located in Northampton County, Virginia.

The Mobjack Bay that the Jones’ passed in 1958 on the way to King-Robins Marina off the York River, as with many parts of the Chesapeake Bay, holds a rich history of pirates and privateering going back to the 1600s that continued well into the 19th century. In Maryland, piracy took place in towns like Baltimore, Fell’s Point, Annapolis, and St. Mary’s City. In Virginia, pirates attacked Richmond and Williamsburg, among many other locations. The reason pirates chose the Bay was because the region’s economy and transportation was based on its waterways, making it an excellent location for imports and exports via ships. Starting in 1612, and for a long while thereafter, three-quarters of the region’s exports was based on the highly-coveted tobacco trade, which was shipped to England, Charleston, New Orleans, and elsewhere. So the Bay was a rich hunting ground for pirates.

Mobjack Bay and the York River

On our Slow Boat to Florida journey, we will be passing by Mobjack Bay on our way to the York River to visit historic Yorktown, as well as the James River for Jamestown. Although any part of the Chesapeake Bay is fantastic and safe for pleasure boating, Mobjack Bay is referred to by its locals as the most peaceful area of the Chesapeake Bay. They say the name of Mobjack for its bay, as well as the small town of Mobjack on its shores, has many interpretations. One is thought to be a corruption from the Algonquin Native American word meaning “worthless earth.” Another has to do with a will dated July 1657 mentioning it as “Mockjack Bay.” Today, the most widely-accepted story behind the name Mobjack relates that when sailors called out over the bay, an echo would come back from the thickly forested shoreline. They said the bay would “mock” Jack (the sailor).

Looking at my favorite chart application, Navionics, it seems that the fish traps that the Jones’ referred to are still there in some way or fashion. On the way down to the south, the Jones’ or Fisher stopped in Hampton Roads and Portsmouth in Virginia. We certainly plan to visit the same spots and compare then and now, but since we’re having a Slow Boat journey to Florida, we also plan to visit Yorktown on the York River just south of Mobjack Bay, as well as Jamestown on the James River. These historic colonial towns on the Chesapeake Bay, just like many others, such as Baltimore, Annapolis, Chestertown, St. Michaels, and Oxford, played an important role in US history. Jamestown was the site of America’s first permanent English colony, established in 1607 in Virginia – that was 13 years before the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth in Massachusetts. Yorktown was where the British surrendered to General George Washington in 1781, ending the American Revolutionary War and securing American independence.

So, we will keep planning and getting ready for more normal years than 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic. We hope that next year, 2021, will be a better year for all of us. I believe in the wise words of T.S. Eliot, the American-British poet, “For last year’s words belong to last year’s language and next year’s words await another voice. And to make an end is to make a beginning.” Thankfully, we have made it to the end of 2020. Now we are looking forward to a new beginning on our way back to “normal.”

A loving wish for a great holiday season and a Happy New Year to you and yours.

Well, that’s it for now. Stay well. I hope to say hello to you if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK, in one of the locations that I’m hoping to visit in 2021, that is if Coronavirus permits us.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

3 things I learned

- Daily life of the American Colonies and the role of the tavern in society was really interesting.

- Jamie L. H. Goodall, the author of Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay, wrote, “As the British attempted to assert their control over the region, Chesapeake residents and merchants began throwing their support behind subversive movements, such as piracy, smuggling and even the push for independence.” Newly-introduced regulations and high demand increased the profits gained from tobacco. That, in turn, increased the desire to grow more tobacco, hence the need to have the labor force significantly grow. And that is where the regions’ enslaved African workforce comes to be. “Pirates were all too happy to provide that labor and steal that tobacco for their own profit,” wrote Goodall. Along the way, European wars between 1689-1697 as well as 1701-1713 helped pirates due to a stagnant economy to import goods from Europe.

- After the American Civil War, the famous oyster harvesting industry of the Chesapeake Bay skyrocketed. While it is now minuscule due to the later devastation of the oyster population, at the time, it was said that each person in New York City consumed 7 ½ pounds of oysters a year. The skyrocketing of oyster harvesting lent itself to oyster pirating. The conflict between oyster pirates, legal watermen, and the Maryland Oyster Navy (the precursor to the Maryland Natural Resources police founded in 1868) lasted until 1959. The Jones’ Slow Boat to Florida trip in 1958 was at the tail end of that Oyster War. Along the way, due to killings and political considerations, the Maryland Oyster Navy was dismantled and led to the formation of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources of today.

1 thing I recommend

- Stay safe, above and beyond anything your health and well being comes first. With your healthy self, trust that in time the rest will fall in place as nicely as you wished for.

How easy?

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL. The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present. My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?