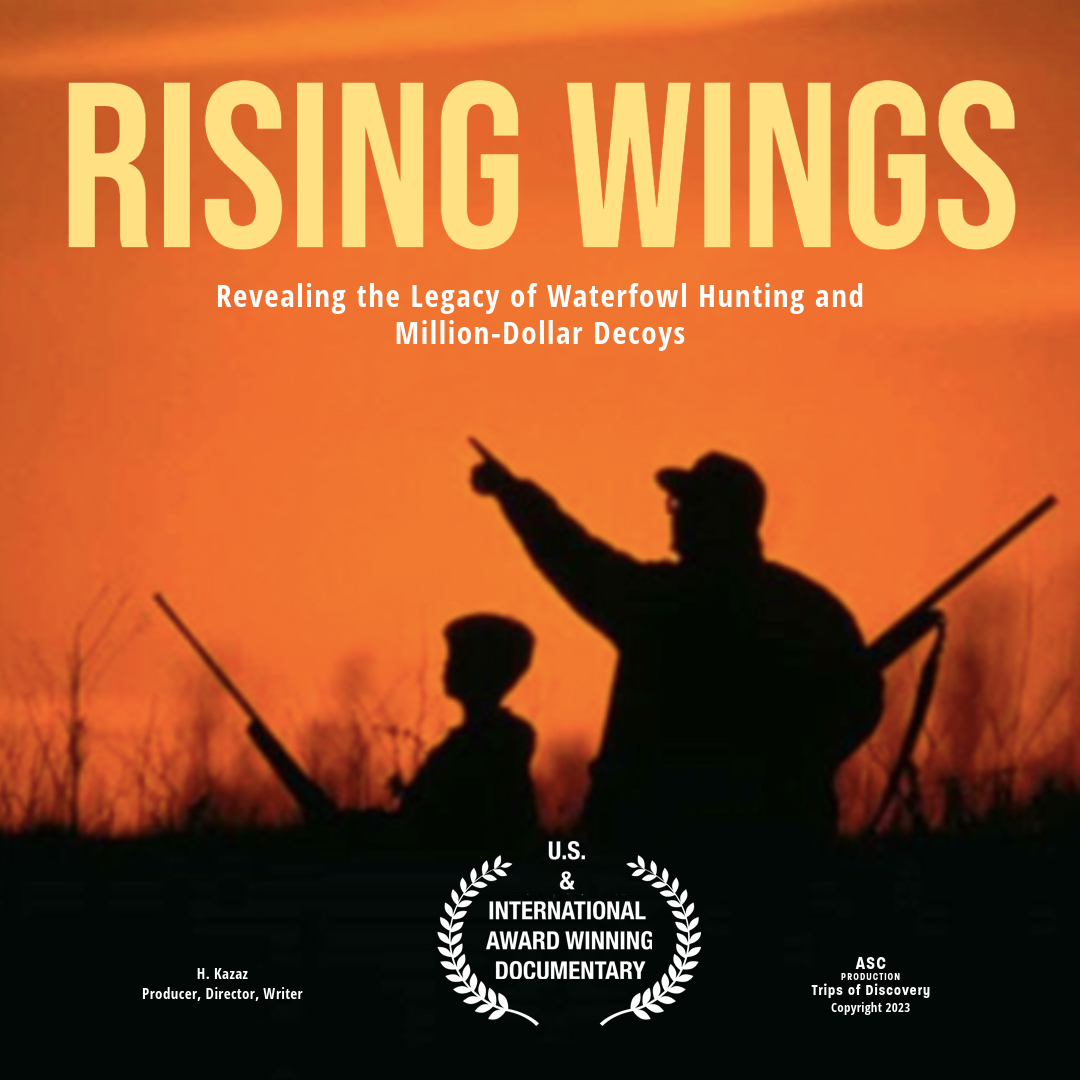

Awesome undertakers, barbers, repairmen, hunters and $1,144,600

This is Part 2 of the previous blog post – A general, bushwacking, body booting and $1,144,600 send me to Crisfield, Maryland.

… Estimated Reading Time: 12 minutes – SBFL 3* – VISITED – Regardless of how you look at it, my story started, without exaggeration, a few thousand years ago, honestly. Definitely not the $1,444,600 part, but the need to build and use some kind of decoy to lure ducks to hunt them has been around in North America at least 2,000 years. I will let Rob Buchanan of Sports Illustrated tell you that part of the story in his 1985 article, “When it came to duck decoys, the Paiute Indians made them to last.” However, I can tell you some of the 19th, 20th, as well as 21st-century origins of references made in my May 30, 2019 blog post.

When I saw a Mallard Hen and a Drake duck decoys by the Caines Brothers had sold for an eye-popping $1,144,600, I couldn’t help wondering what makes these high-priced collectibles so special? Who are the artists, and where and how did they make their living? Where do you find collectible-quality decoys on which one can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars without worrying about their value? Who are the market makers? I was hooked, and I started my research and travel journey. Although I knew that most are long gone, I planned to visit and experience the environments of each of the famous carvers and see their art up close. My first visit was to Crisfield, Maryland, home of the famous duck decoy carvers, the Ward Brothers. The Ward Brothers, Lemuel T. Ward (1897–1984) and Steven W. Ward (1895–1976), were two brothers who became famous for their wooden wildfowl carvings. In November 2006, a Ward Brothers goldeneye drake decoy sold for $109,250.

Market makers

I reached out to Guyette & Deeter, Inc., based in St. Michael, Maryland, which is one of the powerhouses among duck decoy auction houses in the world. They hold more world records than all other auction houses combined in the categories of duck and shorebird decoys, fish decoys & plaques, duck and crow calls, decorative carvings, and shotshell boxes.

The Jim McCleery sale in January 2000 was their largest single sale of decoys ever, grossing over $11 million. McCleery was a famous collector of duck decoys, who made his name by being the first to pay high prices in order to build his collection, starting in the early 1970s. In conjunction with Christie’s, the Guyette & Deeter decoy auction house set the new world record for a single decoy sold at auction of decoy carver Lothrop Holmes (1824-1899) at $856,000. As per the company, their sales in 2014 surpassed $150,000,000. Back in 2007, an Antiques and the Arts Weekly magazine article was already making reference to the skyrocketing auction market.

Undertakers, barbers, repairmen, and hunters

All of the highly-praised and sought-after duck decoys in the collectible market came about organically from talented individuals who needed to make a living through their day jobs, such as an undertaker, boat repairman, watch repairman, barbers, and so on. They were also hunters and hunting guides, not professional artists. They were good with wood and their hands. For example, Madison Mitchell was a funeral director, the Ward Brothers were barbers, and most of the carvers were also hunters. Through their efforts, they ended up creating extraordinarily beautiful, uniquely American folk art.

I asked Zac Cote, Guyette & Deeter’s weekly auction manager, about the famous decoy makers — why did they make them and how were the values for decoys set? He said, “They carved decoys that they thought were going to work best in their environments. They were hunting with those particular decoys. Initial market was set based on who made them, the artist, if the condition of them were fantastic, while taking in consideration the quality of the carving for that carver.” He added, “At that time, everybody did sort of more simpler carvings and if the customer that they were making them for was an important customer, they put in extra effort. Those were the best examples of what they were. They had excellent provenance. They had been owned by the family of the place where they were, the plantation that they were used on over a hundred years ago.”

Today, the most sought-after decoys belong to the famous Elmer Crowell (1862-1952). He lived in East Harwich, Massachusetts. He carved for a living, and also guided hunters and developed hunting camps. Cote says, “When Crowell passed away, his estate was very small. There is a record of his estate; he had a wood burning stove and maybe a hundred dollars or something. That was his estate. Although his carvings can bring upwards of $1 million today, it wasn’t about the money when decoy carvers were carving.”

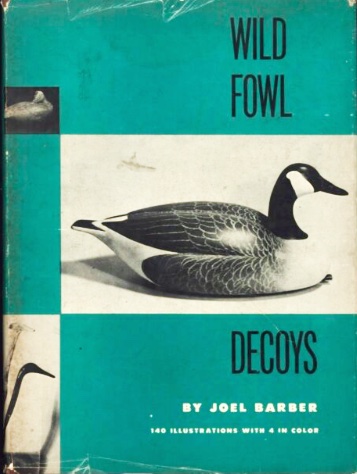

A man who put decoys on the American folk art map

Sometimes the most unexpected chain of events brings out into the open a unique appreciation of beauty within us that is reflected in objects, canvas, or music and brings it to life. That is exactly what happened in the case of decoys. New York architect, author, illustrator, and pioneering decoy collector Joel Barber’s (1876-1952) interest started when he found a battered decoy in a loft on Long Island, says Virginia Kraft in her Sports Illustrated article in 1956. Barber was hooked. By 1956, Barber had already published his groundbreaking, one-of-a-kind Wild Fowl Decoys book in 1934 and had collected a large number of decoys and also started to donate them around.

Guyette & Deeter’s Cote says that Barber’s book was the very first book of its kind and helped support the building of the first decoy collectors market. At the end of his life, Barber donated his famed collection, never before publicly available in its entirety, to a permanent exhibition at the Shelburne Museum, near Burlington, Vermont. As a matter of fact, if you want to get away from it all for a short while, here is an idea for you. There is a very special exhibit in the museum until January 12, 2020, titled, Joel Barber & the Modern Decoy. It is alongside his permanent exhibit in the museum.

So you are not a millionaire, right?

Well, the good news is you do not need to be a millionaire to collect decoys. However, if you are a millionaire and do not want to fly high, you can still get on the collection bandwagon. Cote says, “High six- and seven-figure prices are pretty rare. Yes, we sold them, perhaps a dozen items for over half a million dollars, but it’s not like there’s something in every auction in that price range.” I am told that in any given live auction, 40-60 pieces are in the over $10,000 range and the rest are under $10,000 each. However, if that is still too high for you, Cole says that you can build yourself a nice collection for under $1,000, buying decoys of lesser-known carvers. In fact, when glancing at their website or weekly auction emails, you will notice that there are duck decoys in every price range.

Do you have the wherewithal to jump right into the World Waterfowl Calling Championship and more?

If you want to get away from it all for a short while, here is another idea for you. The Waterfowl Festival this year is coming up on November 8-10, 2019, in Easton, Maryland. It is a kid-friendly environment where you can find something for all ages. It is a celebration of the culture and heritage of the Eastern Shore of Maryland. You will find a unique environment where you can see duck decoys and more. Starting on Friday, November 8, 2019, at 10:00 a.m., you, too, can take part in the World Waterfowl Calling Championship and perhaps be declared a World Champion or humbly just step aside and watch the pros challenging each other to grab the limelight. In some competitions, the top prize may go up $15,000 for first place. Here is the schedule of events for you. By the way, Guyette & Deeter will have one of their live auctions there, a couple of days before the event starts. I am told that it would not be unusual to see up to $100,000 bidding on duck decoys at this event.

Back to the modest world of the Ward Brothers, the Chesapeake Bay

A fondly-known part of the Chesapeake Bay is the Sho’, the Eastern Shore, where the famed decoy carvers the Ward Brothers had their barbershop as well as wood carving atelier in Crisfield, Maryland. This summer I went there, one more time, just to walk around and imagine what it was like living there back then. It is an area where you can walk less than 10 minutes and find yourself on the edge of vast, great marshes splintered by hundreds of mini islands created by river arms snaking across the wetlands while opening up to the Chesapeake Bay. That becomes more pronounced if you look at any aerial photos. Earlier in the Ward Brothers’ life, the bay was a world unto itself, relatively isolated, until the Bay Bridge opened in 1952. Towards the late 1950s, sportsmen all over the United States discovered this fertile land, thanks to numerous articles appearing in the press and books relating to the area.

The area contains the “lordly” canvasback, the redhead, blackheads, ringneck, golden-eye, black duck, mallard, widgeon, pintail, gadwall, teal, bufflehead, wood duck, the various scooters, old squaws, Canada geese, brant, a host of grebes, rudy ducks, and many varieties of shore birds, from the sora rails to the clappers and king rails. If you ask me how to identify them, please don’t, I know only a few that I can identify. For the rest, it is good to do a search on the internet. However, one thing is for sure, each one of the waterfowl requires different techniques in hunting and rigs. Most of these hunting techniques have now been outlawed.

91-years-young retired waterfowl hunter

In Part 1 of this article, you may remember my friend, a great, 91-years-young, retired Army Major General, Warren Magruder, an avid fishing and hunting enthusiast who shared some of his memories with me. I feel privileged to hear and capture his memories of this bygone era. All of his hunting buddies are now deceased.

He remembers his hunting days fondly and misses the comradery while waiting for the ducks. He explained that the canvasback, a large, fast flying duck, was the most sought-after table bird of duck hunters in Maryland. The “sink box” in the famed Susquehanna Flats was the norm. Birds congregated by the millions in years prior to feed on wild celery on the Flats. It is said that when millions of birds flew, it felt like early evening in the middle of the day, covering the light and appeared like a huge smoke plume over the Susquehanna Flats. Times have changed, and the yearly flight to the Chesapeake Bay is now counted only by the hundreds of thousands. Initially lost to pollution and other factors, the wild celery on the Flats is coming back again, but the number of birds is still far lower compared to the olden days. Bird hunting is highly regulated to protect the birds, most hunting techniques are outlawed, and the number of birds any one hunter can kill is severely curtailed.

Tales of duck hunting

One of my favorite books is Chesapeake Bay Duck Hunting Tales by C.L. Marshall. The book’s overview paints a great picture about how it all was and still is. “It takes stubborn dedication and passionate optimism to brave the frosty, wet conditions for the chance to shoot ducks and geese. And yet the tradition continues every year as more than one million waterfowl occupy the waters of the Chesapeake. Whether you are setting decoys or watching the sun rise from a blind, hunting the bay is as challenging as it is rewarding. No one understands that better than the generations who have experienced it, from the goose pits of Rock Hall and Chestertown to the frothing whitewater of the Tangier Sound.”

I hope to say hello to you and shake your hand if you spot my boat, Life’s AOK in one of my locations that I will be visiting.

I bid you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Cover photo: Mallard Hen and a Drake duck decoys by the Caines Brothers. Photo: Courtesy of Guyette & Deeter, Inc.

2 things I learned

- Wild waterfowl have been hunted for food, down, and feathers worldwide since prehistoric times. Ducks, geese, and swans appear in European cave paintings from the last Ice Age, and a mural in the Ancient Egyptian tomb of Khum-Hotpe (c. 1900 BC) shows a man in a hunting blind capturing swimming ducks in a trap. (see Wikipedia)

- There is a huge waterfowl-related world out there, if only you look for it.

1 thing I recommend

- Do an internet search on Waterfowl Festivals and get out there.

How easy?

Do you know any collector who has paid big bucks for a decoy that I can meet? I’d love to interview them and learn more about their passion for decoys.

*SBFL stands for Slow Boat to Florida. It is a series of my blog posts, which started with a posting that had the same title. Each numbered heading has two parts. The first is “Planned,” and when we visit the planned location, a “Visited” label appears at the beginning, next to SBFL. The essence of this series is not to seek new lands and exotic cultures. Rather, it is to cover our journey of discovery (hence the title of our blog Trips Of Discovery) that has to do with seeing with a new eye the coastal locations of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) where present-day America started to flourish. The SBFL series represents part travel, part current and historical anthropological highlights of selected locations and coastal life. We’re comparing then and now, based on observations made by Dorothea and Stuart E. Jones in their 1958 National Geographic article titled, “Slow Boat to Florida” and a 1973 book published by National Geographic, titled America’s Inland Waterway (ICW) by Allan C. Fisher, Jr. We also take a brief look at the history of the locations that I am writing about. Finally, we bundle it up with our observations during our actual visits to the locations and our interviews with local residents. Think of it as a modest time capsule of past and present. My wife and I hope that you, too, can visit the locations that we cover, whether with your boat or by car. However, if that is not in your bucket list to do, enjoy reading our plans and actual visits as armchair travelers anyway. Also, we would love to hear from you on any current or past insights about the locations that I am visiting. Drop me a note, will you?